Traumatic UPJ Disruption Management

The AUA urotrauma guidelines are vague about the management of UPJ disruption. The nearest statement regarding this entity that I could find was:

Surgeons should perform percutaneous nephrostomy with delayed repair as needed in patients when stent placement is unsuccessful or not possible. (Recommendation; Evidence Strength: Grade C)

When the proximal ureter is completely transected or otherwise cannot be cannulated in a retrograde fashion, or if patient instability precludes attempts at retrograde treatment, a percutaneous nephrostomy tube should be placed. If nephrostomy alone does not adequately control the urine leak, options then include placement of a periureteral drain or immediate open ureteral repair

This fortunately gives clinicians that options of both delayed repair or immediate open repair in stable patients. UPJ disruption is very uncommon in adult trauma. Since I have been at University of Utah, the last 8 years, I have treated only the case presented here. Our volumes of blunt trauma are very high with over 70 grade 3 or higher renal traumas during this time. I would estimate the risk of these injuries as <5% in adults. I recently asked Brad Erickson at University of Iowa about this entity during a renal trauma panel and he says he has treated 2 UPJ disruptions. I had yet to see this case and I initially asked if this really happens in adults, promptly a week later my first patient presented.

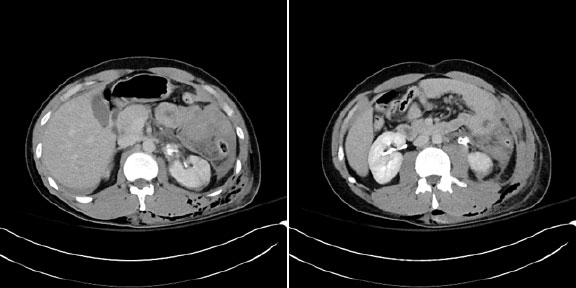

The patient was crushed in the flank and had a colon injury and a grade 4 renal injury. The first CT was very suspicious for a UPJ disruption. Especially the “bulls eye” appearance of the ureteral lumen outlined by contrast extravasation down the sheath of the ureter.

Figure 1 – Initial CT scan showed upper pole segmental infarct (not depicted here) and medial extravasation with outlining of the upper ureter, which looked like a “bulls eye”

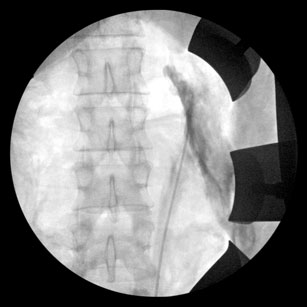

The patient had an immediate exploratory laparotomy and had his colon injury was stapled, we took this opportunity to do a RUPG, which confirmed discontinuity of the upper ureter.

Figure 2 – RUPG demonstrating ureteral disruption.

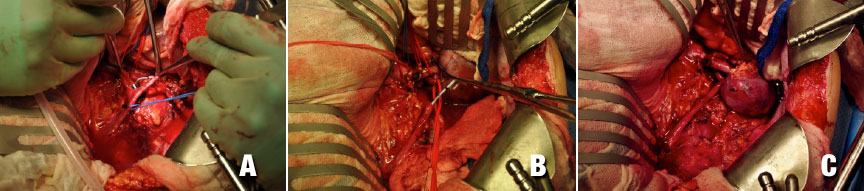

I wasn’t sure what to do, but we decided to try for repair and perform a nephrectomy if this wasn’t feasible given that he had lost ½ of the kidney to segmental infarction. I was concerned about the intrarenal pelvis and how we could access this safely after the trauma.

We were able to flip the kidney upward on the pedicle and access the disrupted pelvis within the hilum. We performed a parachuted repair of the upper ureter into the hilum.

Figure 3 – The first picture (A) shows the stent emerging from the disrupted distal ureter. The second picture (B) depicts the “parachute” type repair and the third the completed anastomosis.

The patient did not leak urine into a JP drain and had a CT scan post op for fever that confirmed about ½ of the kidney remained vascularized and the stent was within the collecting system. We shall see if the repair ultimately saves some of his renal function on that side. A tough problem, but I think in the future I would favor immediate repair as I don’t think we could have accessed the hilum of the kidney after the inevitable fibrosis from a urine leak.

Figure 4 – Post op CT scan at 1 week done for fever shows that kidney has about 50% contrast uptake.